This project began on June 12, 2014 almost exactly a year before my father passed away. That day we had a big tribute concert celebrating him at Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. For all who were there, both performing and attending, it was magical, a spiritual experience. A Who’s Who of artists across all genres were there paying homage, and just freely letting that Ornette energy flow through them.

I was preparing this project for release when my father started experiencing difficulty. His body finally gave way on June 11, 2015 after a brief stay in the hospital. Shortly thereafter, we held a memorial at The Riverside Church here in New York. I had never been to a service where people emerged utterly joyous and smiling. Again, that Ornette energy, so unique and profound, had lifted the room. Defying category, that energy, both down home and highly advanced, is an Ornette kind of authenticity. The service made people feel really good, this window into such a unique being. The words spoken and music played, all from the heart, completed what grew into a yearlong celebration of my father. That is why I decided to put it all together and present it all together here.

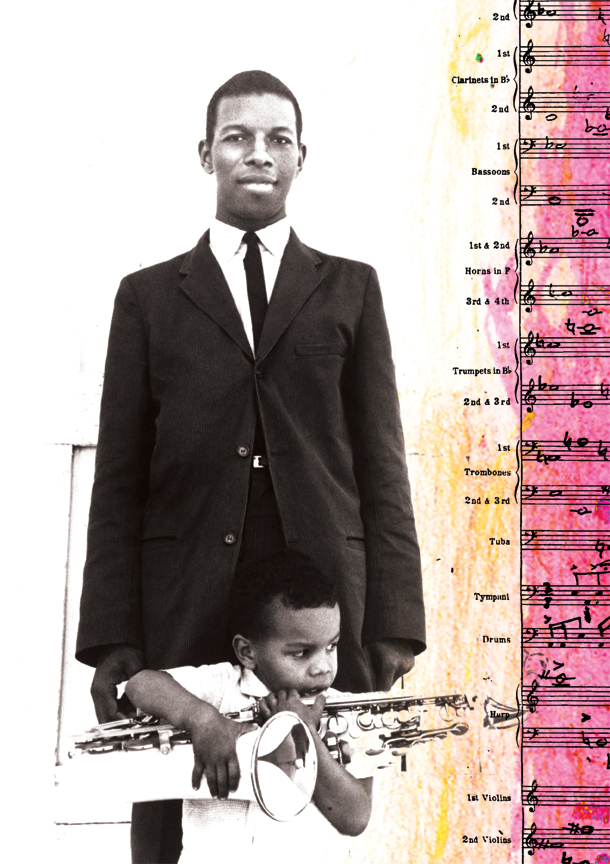

I came to New York with my mother in the fall of 1959, when I was three years old. We were coming in from Los Angeles. New York was freezing. We stayed at the Van Rensselaer Hotel on East 11th Street. (Some things you don’t forget.) We were here because my father was opening at The Five Spot. Of course, I had no idea of the controversy his music was generating. I was equally unaware of it when he and I started playing music together in the garage back in Los Angeles, a few years later. And I was still oblivious to it as a 10-year-old in 1966, when I went with him and Charlie Haden to Rudy Van Gelder’s studio in New Jersey to make a trio record for Blue Note.

But in the space of those seven years, my father had become the talk of the jazz world. He retired, came out of retirement, produced his own concert at Town Hall, began composing for “classical” instrumentation, and recorded and released 12 albums. He devised challenging, provocative titles like, “Tomorrow Is The Question,” Change of the Century,” “The Shape of Jazz to Come,” and “Free Jazz.”

With album titles like that, you would expect to find someone driven by attention, a self-promoter. But to the contrary, my father was an utterly down to earth, humble person. This is why I had no idea of all of the attention he was getting. He just wasn’t driven by notoriety or fame. He was on a mission to be who he was. On a mission to develop his own ideas about sound and about music. At the same time, reflecting generosity and humanity.

My father’s “guys” in those years were Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Billy Higgins, Ed Blackwell, Charles “Diddy” Moffett, David Izenson, Bobby Bradford, and Dewey Redman. By that, I mean I know what they had to go through. The endless commitment to rehearse and explore the properties of sound, sometimes for months without a paying job in sight. The mission, as it turned out, was a spiritual one. Unlocking the energies in music that included healing and higher awareness. Not complicated to be complicated, but sometimes to truly reach the depths of understanding you have to explore, layer by layer, going deeper and deeper. Sometimes people can feel it and follow, sometimes they can’t. No reflection on anything.

I witnessed him doing this month after month, year after year, manuscript book after manuscript book. He would constantly buy these music notebooks, often at a specialty shop near Carnegie Hall. Then fill them up book after book. But these were the guys who went on the journey and into battle with Ornette. I climbed into “the empty foxhole” with them (to quote our LP title,) and was surrounded and protected by all of my uncles on that recording date in 1966. And here we are, 50 years later, still carrying on.

Later on, Ornette’s people would be James Blood Ulmer, Bern Nix, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, Ronald Shannon Jackson, Charlie Ellerbe, Al Macdowell, Kamal Sabir, Calvin Weston, Chris Walker Dave Bryant, Badal Roy, Chris Rosenberg, Brad Jones, Kenny Wessel, Charnett Moffett, Joachim Kuhn, Tony Falanga, and Ms. Geri Allen. The same for everyone, The University of Ornette! He was so prolific that at one period, he wrote new music for each concert. If we had a run of eight shows coming up, we probably played 60 new tunes and five old ones and that’s how it went.

I spent a long time playing with my father, recording, traveling, managing, fighting, endlessly laughing, and going from one exhilarating experience to another. You had to be immersed in Ornette World to realize this wasn’t merely his music — this was how he thought, how he lived. Back in the day we would go real late at night to his favorite Chinese restaurant, at 21 Mott Street, and he would order ten dishes even though there were only four of us. He liked to have lots of different dishes to taste and then to mix together. That’s right, even our dinners were Harmolodic. And forget about giving away the extra food to a homeless person – Dad would see a homeless person on the way home and invite him to sleep at his house.

In the late ’60’s he bought the third floor and ground floor loft space at 131 Prince Street, in what was to become Soho. He called the ground floor Artist House. He put on his own performances there and let other artists put on their own performances free of charge. He put on exhibits of painters he brought in from Africa and other places. It was the sort of open and encouraging environment reflective of his spirit. It went on until the mid-70’s. Then Soho became Soho and the artists were out.

I started managing my father’s career in the 80’s, in my mid-20s. I had been out of college for a few years and playing with him. My father would enjoy a great run of activity and success and then shut it all down for a while, frustrated yet again by the music business. He always felt taken advantage of by managers, promoters, record companies. Finally, I couldn’t sit by and watch the endless cycle of boom and bust any longer. One day I just said, “Let me manage you. You won’t have to stop and wonder if you are being ripped off.” He said okay, and for the next 30 years we did our best to turn ideas into projects.